BRITISH MANDATE

Tegart Fort in Tsfat

The famous Tegart fort in the city of Tsfat — a British-built police station overlooking the Arab and Jewish sections of the city — represented the British colonial presence in Palestine, and the extent to which the British were ostensibly responsible for law and order. These forts can be found all over Israel and the West Bank.

Although British interest in Palestine dates back to the early 1800s, the British assumed an official role in the region during World War One.

Fighting a nasty war against the Germans and their Ottoman allies in the Middle East, Palestine was a highly valued territory for its strategic benefits. The British were therefore eager to court both Jewish and Arab support, and did so by making contrasting promises to both groups.

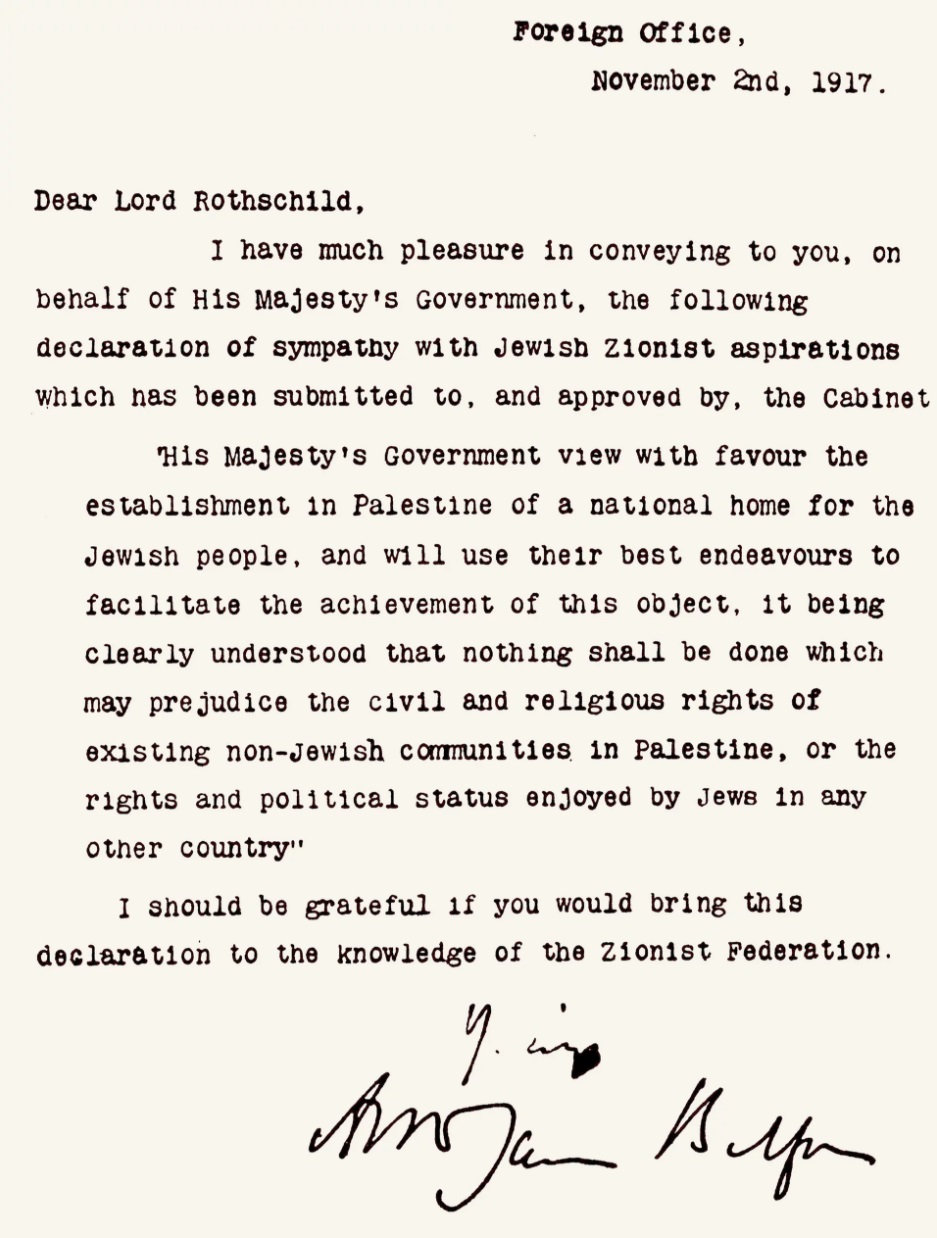

The Balfour Declaration

On November 2, 1917, the British issued the Balfour Declaration, which became one of the foundational texts of the future State of Israel. As a promise to garner Jewish support for the Allied cause during the war, it committed the British to supporting the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Though vague, its 68 words were a profound affirmation of the Zionist Movement’s efforts to achieve international support, and served as the bedrock principle of British policy for the next several decades.

The telegram was sent to Lord Rothschild by the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Arthur Balfour.

Okay, but problem:

Unbeknownst the wider world, the British had made a secret deal with the Arabs back in 1915: that if the Arabs supported the British war effort against the Ottomans, the British would favor the creation of an Arab state in Palestine. But then a year later — a year before the Balfour Declaration — the British made yet another deal, this time with the French.

Called the Sykes-Picot Agreement, it carved up the Middle East into French and British spheres of influence (once the Ottomans were turfed out, of course). But in doing so, the British betrayed that original agreement with the Arabs, a fact which, when revealed at the end of 1917, led to lasting enmity between the Arabs and the West that has persisted to this day.

The British Mandate, 1920-1948

At the end of the war, Ottoman rule in Palestine came to an end after 400 years. The British were in control of both Palestine and Transjordan (the country we today call Jordan). Under the League of Nations, a “mandate” territory is one that is temporarily governed by another power, which then has the responsibility to prepare and facilitate that territory for eventual statehood.

Palestine and Transjordan were combined into a single British colony: the British Mandate (often also called Mandatory Palestine). This meant that the British were officially in charge of Palestine, but could not, say, add Palestine to the British Empire. They had to prepare it for independence. But with both Jews and Arabs claiming that territory, how should the British manage that process?

Map source: the Jewish Virtual Library

Thanks to extensive Zionist diplomacy — led by Chaim Weizmann, who was the the leader of the Zionist Movement at this point — the British favored the Jewish cause in Palestine. British leaders like Winston Churchill supported Zionism; but others were against the Jews, whether because of geopolitical considerations (wanting to keep the Arabs happy because they controlled the oil) or outright anti-Semitism. And in accordance with the 1917 Balfour Declaration, Britain understood that open immigration was essential to the Zionist goals.

But as the Arabs began responding to Jewish immigration with acts of violence, the British began to cave in to the pressure, and see-sawed between restricting and allowing Jewish immigration. This ensured that no one was ever happy, and set the Arabs and the Jews against both each other, as well as the British.

1936-39

A decade of continuous violence and conflict between Arabs, Jews, and the British, culminated in the Arab Revolt of 1936-1939. What began as an Arab general strike under Haj Amin al-Husseini led to three years of bloodshed, as all sides attacked, retaliated, and counter-retaliated for each act of violence. This period had a profound impact on Arab-Jewish relations, Jewish self-defense measures, the British attitude towards both Arabs and Jews, and the long-term viability of the British Mandate.

The Arab Revolt came to an end when the British issued the White Paper of 1939, which all but ended Jewish immigration to Palestine, save for a trickle of Jews who would be allowed in over a five year period. The Jews were apoplectic, as the peril facing the Jews of Europe was becoming extreme, and the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine) was desperate to get as many Jews out as possible. The Arabs, too, hated the White Paper because it still allowed for limited Jewish immigration. The British would hold to the White Paper, more or less, until Israel was established in 1948.

Destroyed Jewish bus near Haifa. Photo source: Wikipedia

The White Paper and Arab violence…

…convinced many Jews that they needed a stronger and more aggressive defense than they had previous employed. This period gave rise to several Jewish militias that met the violence of the Arabs and the intransigence of the British with a range of tools, from self-defense measures to retaliatory strikes to outright terrorism.

Logo of the Irgun